Autism, ADHD, and mental health problems

Life after support from the Early Intervention in Psychosis service

What is psychosis?

Psychosis is a mental health problem that causes people to experience or interpret things differently from those around them. It is sometimes referred to as a loss of touch with reality.

Experiencing the symptoms of psychosis is often referred to as having a psychotic episode. A person might experience it once, have repeated episodes, or live with it most of the time.

Everyone’s experience of psychosis is different but there are some signs and symptoms which may be similar.

The most common experiences of psychosis

- Hallucinations: This is where a person hears, sees, feels, smells or even tastes things that aren’t there; most commonly hearing voices.

- Unusual beliefs: Where a person has strong beliefs that aren’t shared by others, this is sometimes referred to as a ‘delusion; a common delusion is someone believing there is a conspiracy to harm them.

- Disorganised thinking and speech: It may be difficult to follow someone’s train of thought or speech.

- Negative Symptoms: This describes something that has been taken away from an individual’s general mental state, such as a loss of motivation or interest. Individuals may withdraw from those around them, there may be a drop off in attendance and commitment to work, school or college and they may appear emotionless.

These can cause distress and impact a person’s daily life such as attending college, seeing friends or sleeping.

It’s important to remember psychosis is treatable but early signs can be vague and barely noticeable, if something doesn’t seem right then speak with your GP or local Early Intervention in Psychosis service (EIP).

Early intervention improves the rate of recovery and reduces long-term impact.

Many people go on to make a full recovery.

How common is psychosis?

Around 3% of people will experience a psychotic experience, of some kind, during their lifetime. Although an individual can experience a first episode of psychosis at any age, this typically occurs between the ages of 14 and 35.

What causes psychosis?

There is no single known cause of psychosis. It’s likely genetic, biological and environmental (social and psychological) factors all play a part. Each individual will likely have a different combination of these factors.

- Social:

Psychosis can often be a response to things that happen in our lives, particularly traumatic or stressful events. These could include relationships, family difficulties, abuse or loss. - Substance Misuse:

Using drugs such as Cannabis, Amphetamine, or other new psychoactive substances such as ‘Spice’ can increase your risk of developing psychosis. - Biological:

If you have a family member with psychosis, you are more likely to experience the condition. However, the majority of people with a close relative with psychosis, won’t experience psychosis themselves. Various brain chemicals may play a part in psychosis including Dopamine and Glutamate, and some of the causes and treatments of psychosis can influence these brain chemicals. - Psychological:

Life experiences are linked to how we experience and interpret the here and now (beliefs about self, world, and others), negative emotional stages, and coping skills.

Increasingly we see the link between life events and psychosis, with our past experiences, affecting how we experience and interpret things that happen to us now. Psychosis can sometimes have an origin, past events can impact how you experience things that can happen in the here and now. For example, someone who is bullied as a child could develop beliefs that other people may be untrustworthy or likely to cause them harm.

The way that you make sense of things and reach conclusions can also be affected by how you feel. For example, if you are feeling stressed or anxious the way that you view others or the world may be different in comparison to when you are feeling happy and relaxed.

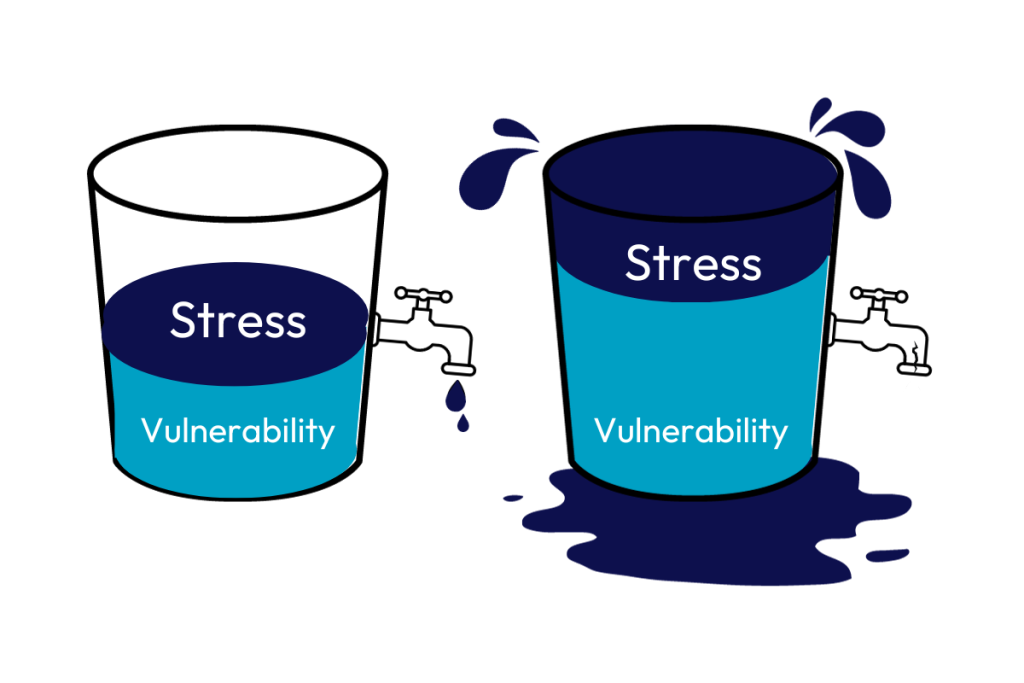

The stress vulnerability bucket

The Stress Vulnerability Bucket This bucket represents your ability to cope with stress. People who have a large capacity to cope with stress and are very resilient have a ‘large bucket’. The size of your bucket varies and is influenced by your biology and your experiences as a child, for example, if you had a difficult time growing up, perhaps due to bullying or abuse then your bucket and threshold for coping with stress may be lower than someone else who didn’t have these experiences. The higher the vulnerability, the less ‘space’ in your bucket for stress.

When something stressful happens or something is worrying you, the bucket starts to fill up one worry at a time. Perhaps you’re having a tough time at college or work, then you get an unexpected bill to pay, and then you find out someone close to you is unwell.

If your bucket gets too full then it overflows and this is when unusual experiences can occur. For example, hearing voices or becoming extremely worried about other people wanting to hurt you.

It’s possible to reduce the stress in your bucket by employing helpful ways of coping. This would be like opening the tap.

Different coping strategies work for different people but good examples are talking your problems through with others or getting a good night’s sleep.

Some things can make the stress worse. This is like blocking the holes in your bucket. Unhelpful ways of coping include taking drugs or drinking too much alcohol.

Another way of thinking about this model is the children’s game ‘Buckaroo’ – the more we added to the donkey, the more stress it feels and eventually it cannot cope any more.

For tips and ideas on helpful ways to cope and general wellness take a look at the Resources page

Phases of psychosis

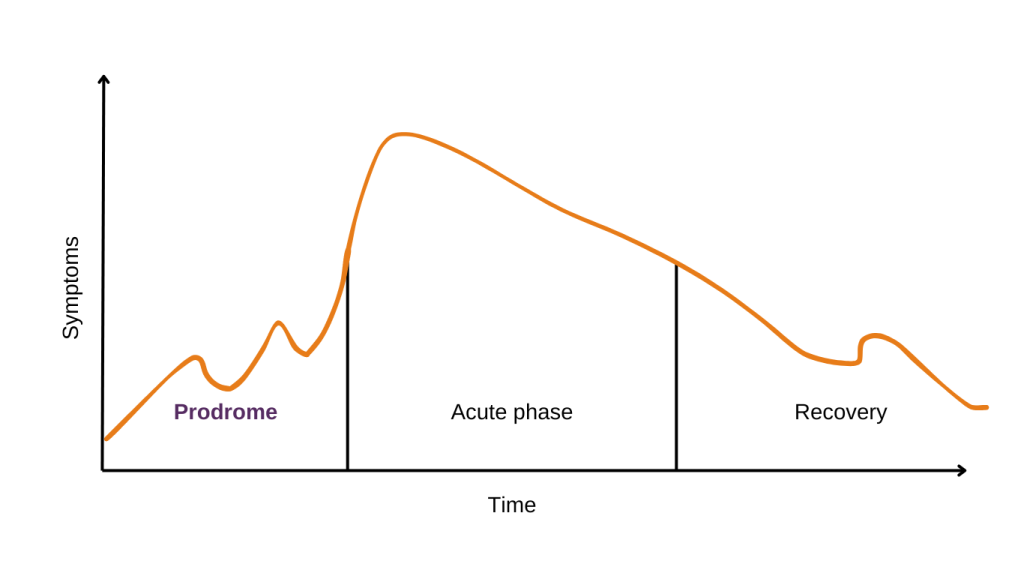

In a typical case of psychosis, it can be thought of as having three stages; the prodromal phase, the acute phase and the recovery phase.

Prodrome Phase

The signs or early symptoms that indicate the onset of an illness are sometimes referred to as the ‘Prodrome’ phase or the ‘Prodromal Period’.

Typical prodromal symptoms are changes in thoughts, feelings and behaviours. It is important to remember that if someone is experiencing prodromal symptoms, it does not necessarily mean that these will develop into an acute episode of psychosis. Everyone’s experiences are different and they will experience symptoms to differing degrees. Some people experience a lot of obvious symptoms and some may not experience any noticeable prodromal symptoms at all. However, there is often a vague feeling that “something is not quite right”.

Often during the prodrome, symptoms will be short-lived, can be hard to notice and may be more obvious to friends or family rather than the individual themselves. As prodromal symptoms can be hard to spot, the prodrome is often diagnosed after the illness moves into stage 2, the ‘Acute Phase’.

Acute phase

During this phase, symptoms can be categorised as ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ symptoms.

Positive symptoms add something to a person’s general mental state such as hallucinations, delusions or thought disorder.

Negative symptoms are considered to take something away from a person’s general mental state, such as motivation to engage in activities, attend to self-care or to cause problems with memory and attention.

Treatment can lead to a reduction in positive symptoms. However, it is more common for some negative symptoms to remain in some form or other.

Recovery phase

This stage will look different for different people. But for everyone, it is characterised by regaining a sense of control over the psychosis with symptoms no longer being the dominant part of day-to-day living. At the heart of Early Intervention in Psychosis Services is the belief that recovery from psychosis is not only possible but achievable.

Work is needed during this time to make sure individuals and their support network are aware of symptoms and what causes them to fluctuate.

This can be achieved by learning about the illness, identifying early warning signs, understanding treatment options available, exploring coping strategies and developing personal wellness plans.

It is important to know that:

- recovery looks different for everyone

- most people make a good recovery from psychosis

Seeking help

You should seek help from your GP immediately if you have concerns about your mental health. The earlier you seek help the better. Your GP may ask you some questions to help determine what’s causing your psychosis. They may refer you to a mental health specialist for further assessment and treatment.

Autism, ADHD, and mental health problems

Research tells us people with autism and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are more likely to experience mental health problems.

Speaking with a clinician about an existing diagnosis or if there are symptoms suggestive of Autism or ADHD will help the processes of developing a patient-centred and needs-based EIP care and treatment plan.

People with autism may interact with others differently, have different sensory needs and need more consistency and routine. People with ADHD tend to fidget a lot, have difficulties concentrating and make impulsive decisions.

Although this is not an exhaustive list, a lot of these symptoms here can impact a person’s thoughts, feelings and behaviours. It is therefore sometimes difficult to separate them from symptoms of psychosis and other mental health conditions.

During the EIP assessment period, the team will be screening for symptoms of Autism, ADHD and learning difficulties. This is to ensure the right care and treatment is delivered to the person.

This assessment will also help inform any reasonable adjustments that need to be put in place.

Further information

Support and guidance around autism can be found on the National Autistic Society’s website. Information on local and national support options and how to connect with other families with similar experiences are available on the National Autistic Society website.

Resources and information on support options and treatments available for ADHD can be found on the ADHD Foundation website.

Young Minds has a page dedicated to ADHD and mental health.

Life after EIP

It is important to consider what life will be like once the support from services has ended.

It is important to consider what life will be like once the support from services has ended. Whilst receiving care from Early Intervention in Psychosis (EIP) service, time will be spent thinking about what will help a person stay well and continue to support their recovery.

Read more on our Life after EIP page.